You know those movies with people talking into headsets? Maybe it’s a heist film and someone’s crawling through an air duct, or it’s a science fiction film and a lonely astronaut is hurtling toward their doom. Whatever the context, that’s the vibe that game designer Tim Hutchings is trying to recreate with his latest project, Apollo 47 Technical Handbook, a one-page tabletop role-playing game with 1,199 additional pages of largely superfluous flavor text. It’s … a bold choice, to say the least.

But Hutchings isn’t just some random developer. He’s the author of, among other things, Thousand Year Old Vampire, one of the most critically acclaimed solo journaling games ever made, a concise and introspective investigation of how the long arc of history weighs on a person’s soul. Bradley University’s assistant professor of gaming design, he is responsible for educating young minds and guiding them into the game industry. A new game from Hutchings is sort of a big deal, even if it’s a weird one. Well, maybe especially if it’s a weird one.

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/23545548/_MG_4012.jpg)

“I pride myself on being an odd jobs person,” Hutchings told me during a recent interview. “Yeah, I used to have — and this is one of my sad secrets — a pretty vigorous showing-artwork-in-galleries-and-museums life. I still do that. I still do all these things, but in a lesser sense since having a kid. [I’m a] Television commercials and strange high-end videos post [production] guys. Last night I was working on opening credits for a feature film for Netflix. […] All kinds of shit.”

The work he most enjoys, though, is designing games.

“The only reason I make games is because games satisfy a need, the creative need, that art never did,” Hutchings said. “And so I bring art thinking — for better or worse, and all the self indulgences and miseries that includes — to the way I think about games.”

With that in mind, Apollo 47 has to be viewed as a kind of commentary on the current state of TTRPGs. Its very existence begs the question: Why do we need an entire library of books, hundreds of pages each, to just play pretend with our friends? It’s that question in part that brought Hutchings from a game with one page to a game with 1,200. It took more than three years, he said, to get things just right. Here are a few excerpts from our conversation, lightly edited for concision and clarity:

Polygon: You said you came to games after becoming somewhat dissatisfied with the art scene. What are the things that art never brought us that you’re bringing with games?

Tim Hutchings: Well, I am not bringing anything worthwhile to the table. I am simply doing that thing where Moe Howard from The Three Stooges falls on his side and he’s running in a circle on the ground and pivoting on his shoulder. That’s what I do, and it makes me laugh. As I do this, many things seem to fly out of my hands and others are able to follow suit. This is what actually happened. Inadvertently, I created a popular role-playing games [called Thousand Year Old Vampire].

With some artistic shrapnel.

Just pure chance that it happened that way.

Now you sent me Apollo 47 on purpose, though. Is this what you are looking for?

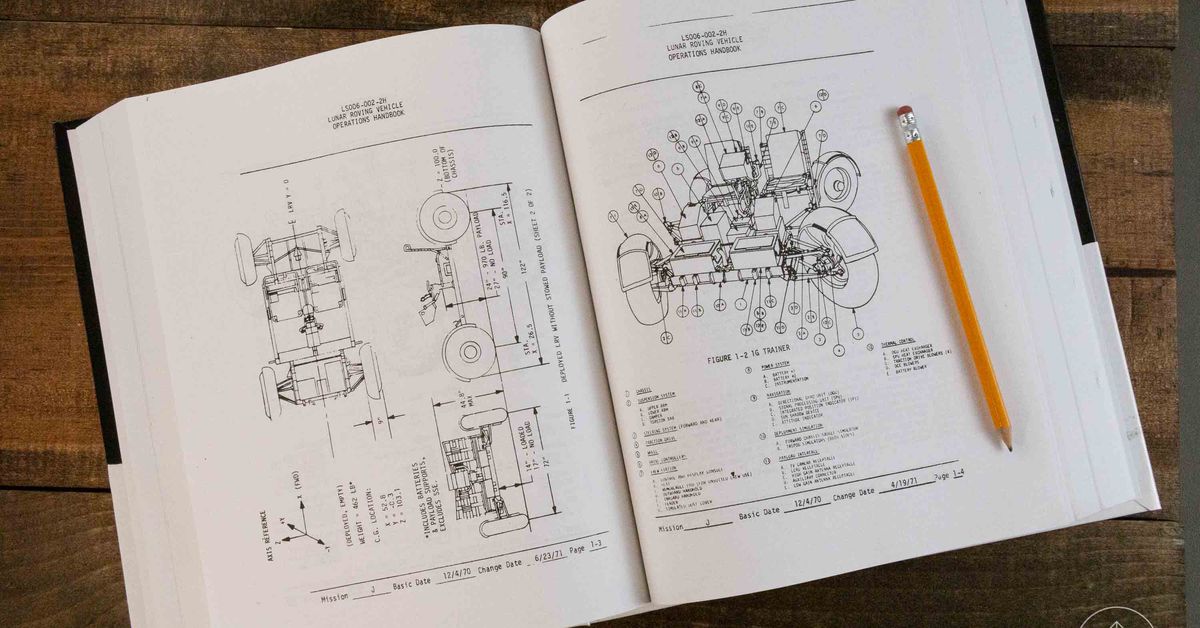

That’s a one-page role playing game. You’ll see it at the very, very, very beginning. It’s kind of like a checklist page with some strikeouts and redactions. And then the rest of the next 20 or so pages are kind of support materials on how to play it right, and maybe some ideas like place names and things you do. And then the other 1,170-ish pages are NASA manuals, in no particular order, that all relate to technical aspects of the Apollo missions, which you can, if you’re so inclined, use as prompts to drive your play.

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/23545550/_MG_4007.jpg)

Tell me how you came to be inspired to write this.

I had been really interested in the kind of communication space of people on headsets telling other people what to do. As if we are doing the heist and I am crawling through the airducts. There should be one to my left, and then I’m directly above the bank vault, right? You’re saying that to me through my headset. I then say, “Well there are bars and I can hear scrambling inside the ductwork.” It’s a great space and it’s something I want to explore.

I kept making these games that just weren’t working, and then at some random point about three years ago I wrote Apollo 47. It was a small game that sat there for quite a while. And then it became that tremendous book. Again, the stupid art spin requires that things that I create have multiple purposes to exist; they can be aware of their own existence; and that they say things that I find interesting about form and format. This was the moment that this one-pager became a hugely overstuffed book.

The thing I was wrestling with is how do you create resolvable conflict within a two-person headset space that is about someone in another room. This was something I struggled with often. How do you resolve this problem? But then I suddenly realized, “Oh, fuck! It’s this NASA headset thing.” It’s not astral projection psychologists from the 1960s and 70s — which was one version of a game like that I made, where they’re describing going through astral projection with one person saying, “Do you see, do you know this shape?” and the other person describing their astral visions, right? There’s so many weird formats.

I don’t work hard. At anything. I don’t iterate. I don’t do all the shit you’re supposed to do.

The vignette that I think of when I think about this is Airplane, and the white zone and the red zone parking where they’re talking over the PA system. What I find appealing about the whole thing is that there’s chatter about what they are talking about but there’s also what they actually feel and how they’re emoting.

What sort of meta layers have been generated in playtesting? What have your players really been discussing with each other while they go through this?

I am not a subtle or smart or a person-with-great-depths. These things do not allow me to see the deeper conversations that are coming from them. However, I am not particularly bright or attentive. Therefore, I have never witnessed people truly dig in and engage in multiple conversations. It’s very absorbing to actually play this — it’s how I understand it in the moment.

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/23545552/_MG_4011.jpg)

Photo: Charlie Hall/Polygon

You’re not being a character. It’s a small, awkward, and verbal area that you are trying to force into. And then people keep changing it and morphing it and the doors keep opening, and then suddenly it expands, and you all find some other thing to do. There is no room for third-tier, subtle play. It’s possible for smart people to do this.

What do you want players to come away from this with?

What are you hoping players will take from this experience, grow or bring with them?

I think one of the really big — because again, my “secret art agenda” is like a Hollis Frampton-esque ability to sit with silence; to sit and just watch systems quietly express themselves, and not have to have anything break the pattern or the system or anything happening. We’re going to watch Zorns Lemma, which is a film where you just watch letters, things that shouldn’t show letters scroll by on a film screen for 30 minutes. What is a game equivalent of that that’s still engaging? Perhaps this could be it?

That’s a huge reach for me to say that. It’s a great skill to have, but I believe that sitting still is something that most games don’t encourage. This game is an example of that. It’s also a very buzzy and hard game for our brains to master. That’s what makes it fun.

It’s also a uniquely Zoom-friendly game, I could totally dial up my friends and play the shit out of this and have a good night.

One of my favorite games [of Apollo 47] I ever played was just phone texts back and forth. It’s super fun and very satisfying.

It’s not that it needs a communications medium, it means whatever communication medium you have, the game can be modified to be people using that communication medium. You could leave notes on a tree and check them each day, or you could just stick notes to the trees with somebody and be like astronauts.

When you play the game, you’re not faking another communication medium. When we play Dungeons & Dragons we’re faking that we’re walking through dungeons and chatting and doing that kind of talk. We’re creating other spaces by doing all of these things. This is how we get into this particular space. We’re in whatever space we’re in, whether it’s the phone, or a video chat, or whatever.

Wow! Wow! We are pretending to be on the radio if we play this game at a table. It’s the best way to enjoy it. Damnnn.

Apollo 47 Technical Handbook is available now as a downloadable PDF, and as a physical book with a pay-what-you-want price. The minimum order is $33. 24 to cover the cost of materials.

Apollo 47 Technical Handbook was previewed using a physical copy provided by Tim Hutchings. Vox Media is an affiliate partner. These do not influence editorial content, though Vox Media may earn commissions for products purchased via affiliate links. You can find additional information about Polygon’s ethics policy here.